November 28,

2017

Discussion: SCOTUS, Carpenter & Call Detail Records

On November

29, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will hear arguments

in the case of Carpenter

v. US. At the heart of the arguments

is whether or not the government (i.e., law enforcement) need a search warrant

to obtain records from cellular providers for suspects in criminal incidents to

help determine the location of those criminal suspects at or around the time of

an incident. Previously, as detailed in

the USA

Today article here, SCOTUS and lower courts have upheld that a search

warrant is not required because the records are not subject to Fourth Amendment

privacy restrictions due to the fact that the data (i.e., the records) are

transmitted to a third party, being the cellular provider. This is what is known as the “Third Party

Doctrine”. It has been cited in previous

cases where a third party, such as a utility company, holds records that may be

relevant in a criminal investigation and the burden of documentation on the

government has heretofore been a subpoena for records, not a search

warrant. Because a search warrant requires

probable cause to be stated, the standard would be higher to obtain the

records.

Think of it this way: Subpoena = “I

want this”

Search Warrant = “I want this, and here is

why”

Call Detail

Records… Sort of

Setting the Records

Straight

I’ve read a

lot online about this case. A recent

posting on PoliceOne.com erroneously leads the reader to believe that this case

is about data contained on the cell phone, much like the often-argued Apple vs.

FBI cases that keep popping up in the wake of active shooter/terrorist

incidents (Read this blog’s take on that here:

https://prodigital4n6.com/clash-of-the-titans-apple-vs-the-u-s-government/

). Let me be clear: This case

is not about cell phone data, forcing people to hand over their passcodes or

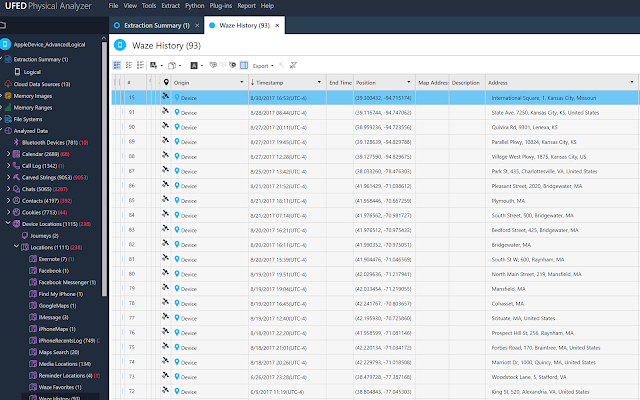

allowing the government to pry into your device! This case is about cellular location data subscribers

virtually never see. It is about records

of cell site location data stored with your cellular provider, along with

sending and receiving phone numbers for calls and texts, duration of calls and

potentially locations of cell sites used for data transmissions when you check

Facebook or your email. You never see

most of this data and if you call your cellular provider, they won’t give it to

you without a subpoena.

To Get A Warrant Or

Not? That is the Question!

Some brief

background is in order before opining on this subject…

I’m a former

law enforcement investigator with 15 years total experience. I worked as the sole investigative member for

my agency on the Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force for several years

and have investigated hundreds of electronically-facilitated crimes, which

meant that I had to author dozens of search warrants and subpoenas. In Virginia, there is a law that allows

police to obtain subscriber information only for users of internet service providers

in child exploitation cases. These “administrative

subpoenas” need to be signed by a prosecutor and can simply be faxed to the

provider to obtain name, address, phone number, email address and any other

registrant information for the user of a screen name, email address, IP

address, etc. It is to be used in child

exploitation cases only and

no additional records are available through this process.

Each and

every prosecuting attorney I’ve ever been trained by or worked with (and I’ve

worked with some of the best at electronic crime prosecution) has a rule: When

in doubt, get a search warrant. In

fact, for cellular call detail records (CDRs), there is often a need to bypass

a subpoena and get a search warrant, especially when requesting more than simple

records – things like text message content.

You see, the law distinguishes between things like simple records and

unique content of text messages, so the burden of the request is naturally higher

when the police ask for content of

email, text messages, etc. vs. simple records of who logged onto the service,

when and from where. It’s an important

distinction and one that SCOTUS will no doubt delve into in great detail during

arguments in this case.

Since

leaving law enforcement and for nearly the past 4 years, I’ve been working

mainly civil cases in the digital forensic field in a litigation support

arena. I’ve also been working cases

involving analysis and mapping of cellular call detail records, so I’ve been

involved in assisting attorneys on verbiage for the requests of these records,

obtaining the records, analyzing the records and using them to prove or

disprove location, link analysis and other items of interest in

litigation. A few of these cases have

been retained by criminal defendants, so I have the benefit of experience at

the prosecution end and the defense end to add credence to the next bit of

information…

It’s very

simple: In most cases, getting a search

warrant helps the prosecution and helps bolster the credibility of the evidence. In most cases where a search warrant isn’t

obtained and that fact is argued by the defense, the arguments help to bolster

the defense and sometimes leads the evidence, such as cellular call detail

records, to be thrown out.

That being

the case, my question to government investigators everywhere is, why not just

get a search warrant anyway?

Yes, there

are exceptions to every “search warrant rule”, exigency being the most

obvious. But absent exigency, a search

warrant should probably be sought.

Investigative Lead vs.

Evidence

Part of what’s

the heart of this argument is whether or not CDRs constitute an investigative

lead or evidence. When police request a “tower

dump” of all devices connected to a particular cell site in a given time frame

around a crime to help generate a potential suspect list or prove/disprove a

suspect was in the area at the time of the crime, that serves as an

investigative lead, but it can also quickly turn into evidence. I would submit that investigative leads alone

do not require a search warrant. By

their very nature, they are lacking in specific evidence in support of them, so

a search warrant likely isn’t feasible.

However, I would further submit that a “tower dump” and the data derived

therefrom also doesn’t fall under the category of a specific subscriber’s

(i.e., target’s) call detail records.

They are records maintained by the cellular provider, but not specific

to any one subscriber.

Only after a

suspect list has been developed and substantial information gathered to develop

actionable intelligence can we start to cross the bridge into evidence. It also cannot be overlooked that sometimes,

cellular location evidence serves to exonerate a suspect, by proving he (or his

device) was not in the area at the time of the incident. Either way, the importance of evidentiary

data in, contrast to investigative leads, dictates that obtaining a search

warrant is likely the prudent move.

Wrapping it Up

Back when

the Third Party Doctrine was originally held, wireless cell phones were just an

idea. In 2017, we use them to stay

connected in our everyday lives. They

help us keep in contact with friends and loved-ones, facilitate banking

transactions, arrange transportation and much more. The devices themselves store a very large amount

of data, but they cannot do it without internet connectivity, which is what the

cellular providers do for us. The weight

of cellular location evidence in both criminal and civil cases has grown

exponentially in the modern era and will only keep growing as time goes on and

cellular networks transition from 4G to 5G technology.

My

prediction: SCOTUS will hold that the government needs a search warrant to

obtain cellular records of a specific subscriber or target of an investigation. However, they need to understand and explicitly

distinguish between records for a specific subscriber needing a search warrant

vs. tools police use to generate investigative leads, for which the burden of the

request should be much lower. Such is

the case when requesting tower dumps. Only

by making that distinction clear will they serve to help answer additional

questions in subsequent cases and put the matter entirely to rest… until next

time!

Author:

Patrick J.

Siewert

Principal

Consultant

Professional

Digital Forensic Consulting, LLC

Virginia

DCJS #11-14869

Based in

Richmond, Virginia

Available Wherever

You Need Us!

We Find the Truth for a

Living!

Computer Forensics -- Mobile Forensics -- Specialized

Investigation

About the Author:

Patrick Siewert is the Principal

Consultant of Pro Digital Forensic Consulting, based in Richmond,

Virginia. In 15 years of law

enforcement, he investigated hundreds of high-tech crimes, incorporating

digital forensics into the investigations, and was responsible for

investigating some of the highest jury and plea bargain child exploitation

investigations in Virginia court history. Patrick is a graduate of SCERS, BCERT, the

Reid School of Interview & Interrogation and multiple online investigation

schools (among others). He continues to hone his digital forensic expertise in

the private sector while growing his consulting & investigation business

marketed toward litigators, professional investigators and corporations, while

keeping in touch with the public safety community as a Law Enforcement

Instructor.