April 5,

2018

About Those Other

Texting Apps in iOS…

In the age

of ubiquitous mobile device usage and the seemingly ever-present need for

digital evidence in the form of text messages to be used in legal proceedings,

we see lots of requests for forensic data retrieval of standard (SMS & MMS)

text message retrieval, Snap Chat messages, Facebook Messenger Messages,

iMessages and the like. What is not so

often discussed is the need for text messaging data from other apps that may

not be as popular or supported by any of the major mobile forensic tools.

Toward that end, this article will explore a sample of them.

To

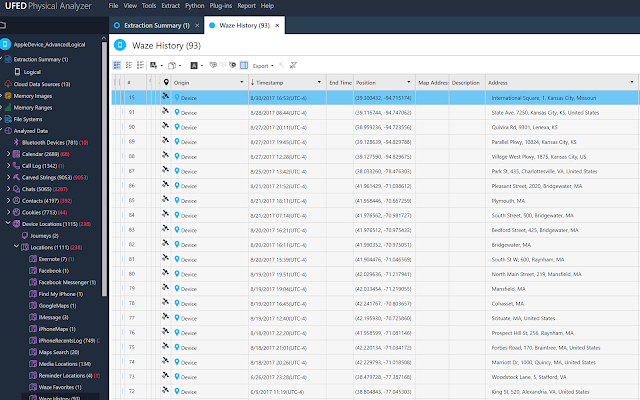

facilitate this analysis, we conducted an advanced logical encrypted data

extraction from an iPhone 8 Plus running iOS 11.3. The extraction was conducted using Cellebrite

Physical Analyzer v. 7.2.1.4. Among the

apps explored are:

Magic Jack: An app used to provide an alternative phone

number to the mobile device. Currently

at Pro Digital, the phone number is through Magic Jack and many clients send

and receive text messages on this number

Sideline: Another app used to provide an alternative

phone number to the mobile device, other than the primary wireless number. Some test text messages were sent using

Sideline.

Discord: An app used primarily by gamers to

communicate. The app has both mobile and

desktop functionality.

Linked In: The popular professional social networking

app, with built-in messaging capability for both mobile and desktop/web

application.

The primary

tool for analysis used was Cellebrite Physical Analyzer, but supplemental analysis

was conducted and information was obtained using Magnet Forensics Internet

Evidence Finder (IEF) v. 6.12.6.

Magic Jack Artifacts

The main

database within Magic Jack that stores not only text messages, but contacts,

phone calls, etc. is storage-##########.sqlite (where the # is the phone number

assigned to the app/device by Magic Jack.

Within that database, the “message” table specifically stores messages

between the user and those contacting the user.

Each conversation with a given party is given a “conversation ID”,

making following of the conversation back-and-forth relatively simple, even if

the party is not readily identified by name or phone number. It is prudent to also note that Magic Jack

does ask for permission to access contacts contained within the main iPhone

contact database and when permission is granted, those contacts are also

present within the Magic Jack sqlite database.

Also notable is the fact that each messages is assigned a “message ID”

in sequential order. This could mean

that if a message were deleted, the sequence would show missing numbers, much

like in the iPhone pictures/images database.

Figure 1

below shows a sample of what the Magic Jack message database looks like in

Cellebrite PA:

Fig. 1: Magic Jack Message Table

Also present

in the “Message” table are dates and times of delivery of each message and the

length (in characters) of each message.

None of this data is encrypted, beyond the encryption of the device

itself. All of this data is also

historical, meaning the data contained in this database has been carried over

through multiple devices.

Sideline Artifacts

An

interesting little nugget that I didn’t know before conducting these tests is

the fact that Sideline is part of the Pinger/Textfree family. The file path for the Sqlite Database in this

instance is “com.pinger.side.line” and the main database where the information

we are researching is stored is “Textfree.sqlite”. In fact, the IEF report viewer lists these

artifacts under “Text Free” as indicated below in Figure 2. This is notable because the Textfree app is

not present on the device, only Sideline is.

Fig. 2: IEF Rendering Sideline as “Textfree”

The table in

which all of the messages are stores is “ZEVENT” and contains not only test

text messages sent to and from the app, but all voice-to-text translations of

voicemail messages. This is very helpful

when potentially researching voicemails that have either been deleted and/or

are not part of the main iPhone voicemail database .amr files. Also of note, as displayed in Figure 3, is

the existence of the IP address with each phone call received and

answered. For example, the IP address of

67.231.9.110 is listed in the table for certain answered calls and renders back

to Bandwidth.com, which is listed on Search.org as being in Raleigh, NC. I’m not exactly sure what Bandwidth.com has

to do with Sideline, Pinger or Textfree, but it does offer another

investigative angle.

Fig. 3: Sideline Database w/ Calls IP

Address Highlighted

Also present

in this database under the “ZCONTACT” table are all synced contacts within the

iPhone by name.

Discord & Linked In Artifacts

Although the

encrypted advanced logical extraction was conducted on the device in this

instance, there is very limited data obtained from both Linked In and Discord,

especially as it relates to messaging.

This is likely due to one of three explanations – the data is either

stored in the cloud, encoded or encrypted (or a combination thereof). For what it’s worth, no large SQLite database

files were discovered with either of these apps, only .plist files and smaller SQLite

databases containing limited information.

Discord, in

particular, is used by gamers, many of whom are children. Investigators involved in child exploitation

investigations should pay particular attention to this app if present on the

device and attempt to document the data by whatever means possible.

Additional Items of Note

While IEF indicates that there is support for Instagram in the “Social Network” category list as seen in Figure 4, there are no recoverable Instagram messages parsed out in IEF:

Fig. 4: Social Networking Support in IEF (Partial)

Conversely, there were many Facebook Messenger messages obtained by IEF as

detailed below in Figure 5. This is of

particular note as many have asked across digital forensic list serves about

the potential presence and recovery of Facebook Messenger messages. While not every bit of information is readily

apparent in IEF (i.e., the other party involved in the message), identifying

the sender and receiver is a simple matter of looking in the detail tab to

identify the Facebook user IDs involved in the chat.

Fig. 5: Facebook Messenger Messages

in IEF

Conclusions

Those of us

familiar with the strengths and limitations of the commonly used commercially

available mobile forensic tools know their limitations very well. Experiments like these start to push us

beyond what is natively supported and help us take a deeper dive into the data

to see what (sort of) hidden gems exist beyond what is served up on a silver

platter. There’s a ton of data out there

to be had. Companies like Cellebrite,

Oxygen, MSAB and Magnet Forensics can’t be expected to support every version of

every app. It’s simply not possible, or

if it were, the costs for these tools would be astronomically higher than they

are now.

It is

incumbent upon the examiner to know what to look for, where to look for it

(i.e., how to find it) and how to read and interpret what they find. Missing valuable data can mean the difference

between determining culpable or responsible parties in civil matters or not and

in criminal cases, could mean the difference between guilt or innocence.

Author:

Patrick J.

Siewert

Principal Consultant

Professional

Digital Forensic Consulting, LLC

Virginia

DCJS #11-14869

Based in

Richmond, Virginia

Available Wherever

You Need Us!

We Find the Truth for a

Living!

Computer Forensics -- Mobile Forensics -- Specialized

Investigation

About the Author:

Patrick Siewert is the Principal

Consultant of Pro Digital Forensic Consulting, based in Richmond,

Virginia. In 15 years of law

enforcement, he investigated hundreds of high-tech crimes, incorporating

digital forensics into the investigations, and was responsible for

investigating some of the highest jury and plea bargain child exploitation

investigations in Virginia court history. Patrick is a graduate of SCERS, BCERT, the

Reid School of Interview & Interrogation and multiple online investigation

schools (among others). He is a

Cellebrite Certified Operator and Physical Analyst. He continues to hone his digital forensic

expertise in the private sector while growing his consulting &

investigation business marketed toward litigators, professional investigators

and corporations, while keeping in touch with the public safety community as a

Law Enforcement Instructor.